Dear readers,

Welcome to the third in our series of ‘Lay it on the Line’ collaborations. With this one we are diving deep. Yasmin Chopin opened a drawer and with her invitation (and this month’s curation) came a flow of existential sediment and ponderings on mortality. With each one of us sliding gently open a drawer of grief and care. The synergy of our writing is growing and I find myself surprised by what wishes to be shared. Warmed by the magic of it, how written words can share such depth with new friends so soon. It makes me long for days of hand written letters but this is a new form, you, the reader, are welcome too.

Buried in a Drawer by Yasmin Chopin

Some weeks after my father died my brother and I had to clear his flat. We deliberated on what we found in every drawer and cupboard—each represented a multitude of decisions. Keep, donate, auction, tip. We composed lists.

I came across a trio of lavender-infused egg-shaped soaps nestled in a box—a gift I presumed, not for my father but for mother who had died a decade earlier. Should I preserve them as my father had done? What would mum have wanted? I took them home and embarked on a ritualised performance of hand-washing. I gained temporary solace from the smooth ovoid shapes, from the froth and suds they produced as I massaged my hands in their lather. Lavender was her favourite; she would slowly inhale the scent as though it had a nicotine kick, and looking me in the eye she would smile and exhale.

We sorted through the richer pickings and began a slow bagging up of the residual flotsam, all that was left of a working-class life racked by illness. Dad’s Welsh Guards' blazer hung stiffly behind mirrored wardrobe doors, a smart fit, worn to many funerals; in this item of clothing his presence was palpable, we had to keep it. But we let the six ribbon plates that lined the mantelpiece go. And the onyx-topped coffee table with its bruising brass legs. And the dozens of suitcases stacked and filled with the canvases he’d painted during an industrious retirement.

The contents of a house, a cupboard, a drawer, all serve as mirrors to a life once lived, a biography of sorts. Every object conveyed a treasured mnemonic potency, having the capacity to remind me of past events and feelings—memories that I knew would adjust and shift over time. In a larder of hoarded groceries, I found several hundred tea bags and realised that, as I worked through this cache, I would be measuring the progression of my grief in cups of tea.

By Stacy Boone

I remember moments when two people conversed about, well anything, in front of the lavender. Its etymology traces from lavare from lavo (to wash) and maybe that is what happened outside chatting in the presence of lavender. An unintentional act not of washing in scented water but the cleansing of one’s spiritual aura. Or, at the very least, the sharing of a burden, and in turn a sense of meaningful belonging.

~ ~ ~

The lavender leaves are a shade of pewter, turned unruly with neglect. Yet, she survives, even as a skeleton of her possibility, a fraction of her significance. Each clump wiry, brittle, overextended. No upright spikes of tender leaves invite touch. Instead, a crudeness that deters a grazed finger to gather her calming microscopical oils.

In the spring, I speak to the lavender before cutting her underneath limbs and trimming to reshape her wholeness. With clippers, I remove not quite half of her woody base; I fret my effort is in excess and can only wait.

In the summer, temperatures warm. Light green, elongated, narrow leaves reach for the skyline. The lavender thrives with spikes, each calyx a pledge, each corolla a glimmer in the rays of sun. I nip selected spikes and wrap them in tissue paper to include with a hand-written note—snail mail—the recipient will value the gift.

In the evening, I snip more spikes and pluck individual flowers. In a bowl, I blend 1 ½ cups of flour, 1 teaspoon of baking powder, ¼ teaspoon of salt, ½ cup of butter, 1 cup of sugar, 2 large eggs, 2 tablespoons of vegetable oil, 3 teaspoons of vanilla, and ½ cup of milk. I add the lavender until the balance feels right and bake at 350-degrees for 20 minutes.

In the morning, my hands hold a piece of cake and a jar of homemade rhubarb-strawberry lemonade. A gleeful hello to a neighbour deserving of companionship. More than treats is the largesse of time listening to stories that might otherwise be forgotten. Meaningful belonging, with a hint of lavender.

Artifacts by Julie Snider

In my home office, there’s an antique lawyer’s bookcase. It’s perhaps one hundred years old, oak, stained a medium brown. On its third shelf sits a small collection of family treasures.

There’s my father’s pocket watch, the timepiece he carried as a railroad employee. The watch sits under a tiny glass dome, suspended from a peg in its center. Ironically, Dad literally ran out of time, dying less than a year before he was eligible for retirement.

Next to Dad’s watch is a small Cobalt blue Shirley Temple glass, a 1935 giveaway from Bisquick Baking Flour. My mother’s name was Shirley, and she was six years old in 1935. Did her mother give it to her, or was it passed down once Grandma died? It feels like I’m holding a piece of her childhood when I cradle this four-inch cup in my hands.

There’s a snapshot of our dark blue 1968 Ford Falcon station wagon with a silver bullet-shaped trailer attached. Mom wrote on the back of the photo: “The Sniders, home from the Smokies-7/68.” Clipped to the opposite side is a picture of me standing between my parents. It’s 1980, and I’ve just graduated with a degree in music. Wearing cap and gown, I have one arm draped over my mother’s shoulders. Mother looks very proud. Dad is on the other side of me, hands behind his back in an almost military stance. His light blue leisure suit, complete with vest, was the same one he wore to the horse races.

The pocket watch, the Shirley Temple glass, the photos—they ground me. Like a warm sweater on a chilly day, I pull the memories close. I wonder: What artifacts will mark my existence when I’m gone? Perhaps a cake of rosin, a bird figurine, and a novel. Perhaps nothing at all.

By Julia Adzuki

After the funeral we went to her house. She was still in the air, gathering as dust on the furniture, our great Aunty May. We opened her cupboards and began unravelling the traces of her. Spinster and seamstress, she'd taught my mum to sew and my mum had taught me. Kindness with a cheeky smile that broke through her reserve. In the top cupboard I found her felt hats and dressed the whole family in a rainbow array; grandpa, mum and dad, sister, cousin, uncle and aunt. There was a bursting open in that moment, reverence in irreverence, alive in her wake.

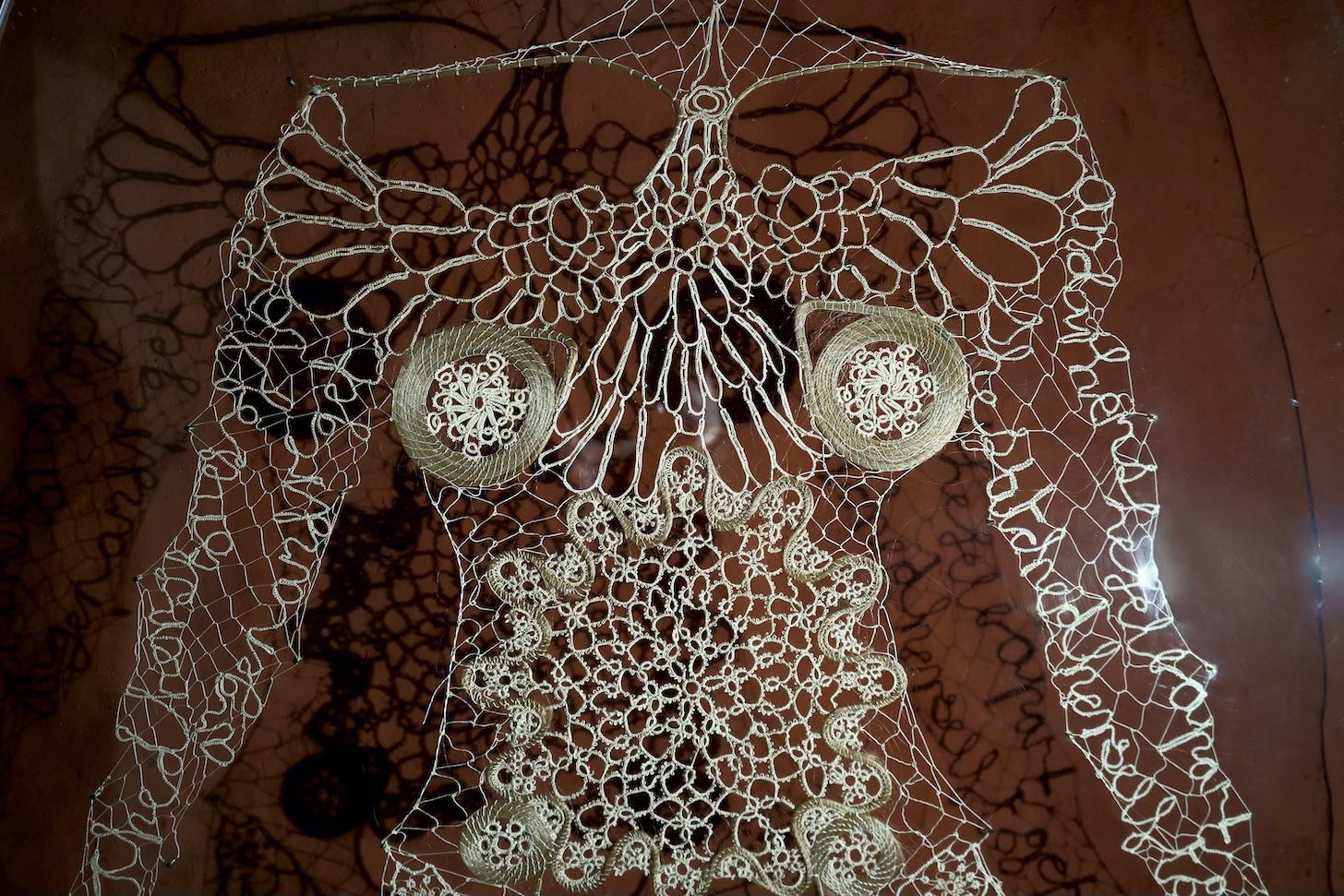

I found a thick plait of hair from her youth and lace she'd made with tatting shuttles. Took my treasures home to Tasmania where a friend taught me to tat. Doilies, looked to me like cellular structures under a microscope, bodily tissues. Working knots over thread and wire, I made a life-sized woman, dedicated to Aunty May. A bird for the chest, fish in the legs, embellishments with our hair stitched together. Embedded in the arms I tatted the text - 'She stitched her love, pain and regret and when she fell apart, she stitched herself together again'.

The day she was ready, I delivered her to Moonah Arts Center, for the Women's Art Prize exhibition. I'd decided that if I won I would buy a ticket to Europe, and that is exactly what happened. While traveling in Estonia, Finland and Sweden I loaned her to the Women's Health Center. Ten years later, still living in Sweden, I decided to donate the work permanently. 'Tatted Secrets of my great Aunt May' had been a healing companion to clients, doctors and therapists for 18 years, at the time I fell ill with encephalitis.

I woke up in hospital on intravenous antivirals. The day before was a blur, having lost the ability to walk, speak and then lost consciousness. When I was cognisant enough to look at my phone, there was a message from the Women's Health Center. They were rebuilding and no longer had space for the tatted woman, would I like to have her back? Yes! She became my healing companion. Shipped to Sweden by my mum, hanging by my bed as I gradually recovered from inflammation in my brain and spinal cord. A gentle reminder that I too could stitch myself together again, and that I have.

By Amanda C. Sandos

Sitting slumped on the couch, sound asleep, mouth wide open, eyes wide shut, the shell of my mother is once again napping. She sleeps most of the time, now. When she is awake, I still catch glimpses of her, in the briefest twinkle in her eye, or a little giggle of a laugh, when and if I can uncover her humor for a moment. It is still there. It will still come out to play, briefly.

This morning, she asked me if I could explain to her what had happened to her mom and dad. Generally, when she frames the question in this way, she remembers they are gone, but not when or how they died. This time, though, when I said they both lived long lives and died in their elderly years, she flinched like I had slapped her and began to cry. She had been thinking they were still alive and living in Roanoke. Until I killed them for her. Again.

Generally, if she asks the dreaded “have you talked to them” question, I just say something like, “Not lately, but I will tell them you asked about them.” If only I could take back my answer today. Or better yet, fast forward mom through this terrible dementia so she can finally rest. But this morning, I held her while she cried, and swallowed my own tears with every ounce of will. If I let them flow, I fear they might never stop.

Where is my mother? Do you remember what happened to her? I wish I knew what happened to her. I wonder when I will be asking that question, and who I will be asking it to. I don’t have any children, and my partner passed away in 2019. It’s just me, once mom is gone. I mean, I have an older brother, but he has not showed up to see his mother even once since this began three years ago. So, when the dementia comes for me, as it has for every single woman in my family for decades, I don’t have a clue who I will ask.

For now, as I sit listening to mom’s soft snores, I tell myself to focus on treasuring the moments when I see that glint shine in her eyes again. I can still coax it out by whispering conspiratorially about a secret I am keeping, like we’re little girls together, best friends sharing important truths. But my biggest secret, the one I can’t ever tell her? I miss my mom with a deep chasm of longing even as she sits right in front of me, soundly asleep.

By Bee Lilyjones

By Donna Fisher

I used to shun rituals. They felt too binding, restrictive. I hated the expectancy of birthdays — the cake, the song, the presents. The structure and order of religion felt suffocating. Even my inability to finish The Artist’s Way, I think, came down to its rituals; morning pages felt like torture.

Then my father died. During a pandemic. And I was on the other side of the world.

The comforting refrain I’d sung for the past twenty years — it’s only a plane ride away — fell as silent as the skies above Australia.

I told myself it didn’t matter that I couldn’t attend the funeral. I’d still write Dad’s eulogy. I’d still be there, via Zoom. But as I listened (through a propped-up phone) to someone else read my words and watched the twenty mourners leave the church, my mother being held up by my sister, grief landed on me. Like a sodden, misshapen lump of clay. Which I didn’t know how to mould into something strong enough to carry my sadness.

For a year, I tried. But it was like sitting at a pottery wheel without a teacher — not knowing how much pressure to apply, where to place my elbows, how to use my fingers to shape the form. I hadn’t gone through the rituals that teach you how to handle grief: organising a funeral, clearing out belongings, sharing stories at a wake.

So what I was left with were shelves of odd, unfinished things. Cracked through with denial. How could he be gone, if I hadn’t said goodbye?

And then, when I could finally travel, all those cracked vessels shattered.

For the first time, I walked into a house that didn’t smell of Old Spice. His familiar mug wasn’t on his little table. His hand wasn’t on my head. He was not there.

Gently, my mother guided me, and my grief became more cooperative in my hands. A box of photos. ‘Do you remember when…?’ A bolo tie he’d loved, handed to me.

An urn, taken to a beach. One last family trip Dad had waited to take until I could come too.

As I watched him dance on the breeze, above his favourite stretch of ocean, I felt my grief take on a shape I recognised. A mug-shaped thing, full of warm memories. A mug I can sip from whenever I miss my Dad.

In Conclusion

You are welcome to leave a comment here, or to comment on Yasmin’s original post.

What memories do you keep in your drawer of grief?

If you missed the first two posts in the ‘Lay it on the Line’ series, you can find them here…

#1

#2

We hold hands around the world. It’s a pleasure writing with you Amanda.

Yay for posting from the other side of the planet. This made me smile when I saw it so thanks for that just as I drift off to sleep.